I’m standing outside of the El Paso International Airport, trying to find the van that’s going to take me to Ciudad Juàrez, Mexico in the state of Chihuahua. I called the number I have for the driver who was supposed to pick me up. He told me he will be here in a minute or two in a “van with a cracked windshield.” So I’m standing underneath that big west Texas sky, and I think that maybe I’ve made a mistake coming here.

I am about to ride the short distance across the border to Juàrez, a city that has been labeled the “most dangerous city in the world” by at least one U.S. official. It’s a place where the President of Mexico, Felipe Calderon, sent 2,500 army troops in 2008 in an attempt to restore order, and failing, sent in more troops the next year. It’s a place where the chief of police resigned after the cartels kept a promise to kill a police officer every 48 hours until he did. It’s a place where midday murders were common and bodies were hung from power lines to send a message. It is a place where government and law officials were given the choice of “plato o plomo,” Silver or Lead, bribes or bullets. It’s a place where all of this happened; it’s a place where all of this used to happen. But does it still? I had heard of “Plato o plomo” before, from a cab driver taking me to see Pablo Escobar’s grave in Medellin, Colombia, a city that had also been brought to its knees by drug violence, but is now known for the “Medellin miracle,” and as an example of third world economic development. Could Juàrez be in the middle of a similar turnaround? Had it happened already? And if it had, would anyone notice?

The van comes. There is not a crack in the windshield. There are hundreds. It is completely smashed. I get in and we head toward the source of Juàrez’s past glories and suffering, and what a few passionate people hope will be the source of the city’s resurrection. We head for the border.

Dave Hensleigh is a man on a mission. He walks into the Juàrez Best Western and addresses a table of groggy and slightly hung over travel writers with a smile. It’s 9 a.m. on Dave’s 63rd Birthday and he’s wearing running shorts, a “Raramuri Running Project” t-shirt, and a medal around his neck. He has just run a half marathon through the streets of Juàrez and he is telling us that he is going to grab a quick shower before we pile into a van and head south to Chihuahua City,where we will board the El Chepe train and ride it to and through Copper Canyon, Mexico’s breathtaking Grand Canyon equivalent.

Dave runs Authentic Copper Canyon, a tour agency that takes small groups on customized trips throughout the region. He took over the company in 2007, and he now offers specialized tours for everybody, a running tour, a Soto (a local, delicious, liquor and already the next big thing) tour, hiking tours, foodie tours, pottery tours. You have an idea and he’ll work with his network of locals to create an itinerary. He looks energized in spite of, or maybe because of, having just run 13 miles before 9 a.m. on an empty stomach. “I gave all my gels to the Indians,” he tells us “I need to get some food.”

In August 2011, Dave did his best to dispel the perception that Juàrez is the most dangerous place on the planet. He walked across Juàrez. It took him three days. Dave looks like a tenured college professor who coaches the local track team in his spare time. He’s tall and skinny and his glasses rest on top of sharp features that are always configured to set one at ease. He’s a former preacher, a fact that he never even hinted at until I pull it out of him. But it makes sense given his propensity for using the exclamation “my goodness!” and his fondness for calling things he cares deeply about, the Mexican people, Copper Canyon, and especially Juàrez’s resurgence, “miracles.” All this is to say that Dave looks very much like a gringo, and not especially intimidating. And yet, nothing happened when he walked across the city, other than Dave had a great time. “I never felt more welcome or encouraged, “ he said.

At the MUREF (museum of the revolution on the border), a middle aged white woman approaches me and the group of writers and travel agents I am taking a tour with.

“What are you doing here?” she asks.

“We are taking a tour. Some of us are writers. They’re showing us that Juàrez is safe.”

Before I can ask her if that’s true or not she jumps in.

“Good. I’m the only Anglo I know who comes here. I love it. I love Juàrez. I’m showing my friend from out of town that it’s safe here. She was brave enough to come with me.”

It’s easy to see why Americans are so skittish about crossing the border these days. Just take a look at some of the official government sources on the relative safety of Juàrez and the state of Chihuahua. This travel warning is from the State Department website, dated February 2012:

“You should defer non-essential travel to the state of Chihuahua. The situation in the state of Chihuahua, specifically Ciudad Juàrez is of special concern. Ciudad Juàrez has one of the highest murder rates in Mexico. The Mexican government reports that more than 3,100 people were killed in Ciudad Juàrez in 2010 and 1,933 were killed in 2011. Three persons associated with the Consulate General were murdered in March 2010. “

That is what’s currently on the website. But during October 2012, there were only thirty murders in Juàrez, the lowest monthly murder total in five years. And it wasn’t an outlier. That is part of a trend that has shown the murder rate drop 45% in 2011, and numbers show it’s on pace to decrease that much again.

Even the U.S. Government seems a little confused about just how safe Juàrez is. “Juàrez is today the most dangerous city in Mexico and I think it’s the most dangerous city in the hemisphere, if not the world.” That’s what William Brownfield, the Assistant Secretary of State for the Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs, said to a U.S. congressional panel in March. (To which Hector Murguia, the Mayor of Juàrez replied: “We’re not the world’s most dangerous city by a long way, nor Mexico’s, and we can prove it.”)

But just a few days later the U.S. Embassy in Mexico applauded joint U.S. and Mexican efforts to combat the drug trade, and noted increases in safety. “The impact of these efforts can be seen in (Juàrez’s) crime statistics, which show a significant reduction in homicides,” the embassy said.

All statistics aside, Juàrez hardly feels like the most dangerous city in the world, nor does it feel like a particularly dangerous city at all. Murder statistics are down significantly in 2012, but what really is noticeable is how the public squares and markets seem like any other. I am told they were empty just a year or two ago. People seem universally certain that the drug violence is over, that everything is getting better, and that the only thing lagging behind is public perception. They want Americans to come again (there’s a statue of Lincoln that’s visible from my hotel). Bordering the world’s most powerful country will always afford opportunities. The problem is when the opportunities are the wrong ones, which they have been for too long.

The border itself is not that hard to get across legally. You can walk over the bridge or drive, and there can be a line, but it took us probably twenty minutes to get from El Paso to Juàrez. There are special permits and stickers you can get to go back and forth regularly, as many people work or go to school in El Paso and live in Juàrez, and, more and more, as investment returns to Juàrez vice versa.

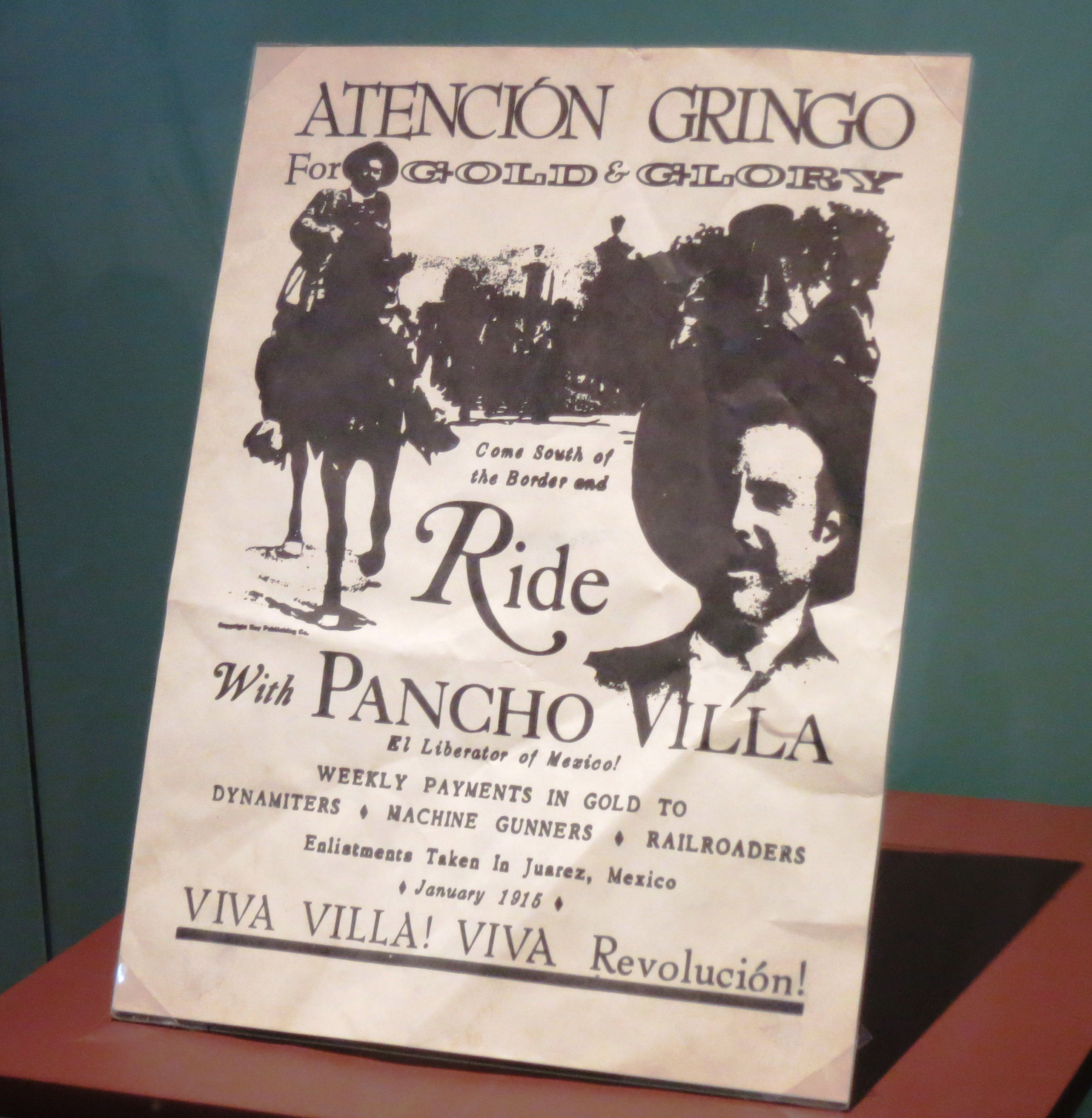

We take a tour of the city with Julian Alvarez, a professor of Tourism at Juàrez University and a part-time tour guide with Chihuahua Tours. His accent is undetectable, and he is a walking Wikipedia page on Mexican history, especially the history of the revolution. We visit an adobe house that sits a on the outskirts of town just few feet from the Rio Grande. It’s a historical landmark and its two rooms serve as a sort of museum/recreation of the era where leaders of the revolution, like Pancho Villa and Emilio Zapata, launched attacks against the Mexican government from here, and would slip into Texas when the authorities closed in.

The house is a few feet away from the border, from both borders. Juàrez is actually bordered by Texas and New Mexico. The Texas border is very clear. There’s the Rio Grande, which is nothing more than a stream which some Mexicans are standing in and catching catfish the day we are there, and there’s the giant border fence on the far bank. The locals call the border fence the El Muro de Verguenza or “Wall of Shame.” It’s huge and actually does manage to straddle almost the entirety of the U.S-Mexican border. Julian tells us that much of the material for the fence was used during the Iraq War. From the adobe house, it’s clearly visible and it’s a serious deterrent.

But the New Mexico border is different. And it also stands a few feet from the adobe house. There is no fence, except a tiny rope that is strung a foot of the ground around a white stone monument that has two plaques on opposite sides, one in English and one in Spanish, marking the border the way one might mark a historical or geographical oddity. You can walk into the U.S., which is technically illegal. It’s hard not to feel the absurdity of the same national boarder being protected by a giant tax-payer funded fence just a few a few hundred yards away from where the same border seems to be treated as a photo op.

But there is the Border Patrol SUV, sitting between the two. I can’t tell for sure, but I swear from where I was standing it looked like there was nobody in it.

We drive around town and Julian insists some neighborhoods we pass are “safe, but not ready for tourism.” Juàrez was once a bustling border town, and it boomed when the U.S. enacted prohibition. There’s an old whiskey distillery, now boarded up but still standing, that was owned by Al Capone. Julian tells us that the city also became a sort of reverse Vegas during the fifties and sixties before the advent of no fault divorce. People could come to Juàrez, stay a few nights, and get divorced. There were bars and clubs as well. It was its own kind of sin city.

Even into the nineties the tourists still came to Juàrez. “The 90’s were a boom, with thousands and thousands of people coming. It stopped,” Dave told me. “But it will start again because this place is a miracle.”

Everything went south in the 2000’s. In addition to the violence, there was swine flu, which drove tourists away and hurt agriculture, and the economic crash, which also drove tourists away and resulted in sudden closures of Maquiladoras, the free trade zone factories that supply Americans with all sorts of cheap goods. Those closures left people unemployed and desperate, creating an optimal situation for the cartels to recruit soldiers. There were more bodies than ever before to move the drugs north, and move the guns south. I learned from Julian that due to a treaty with the U.S., Mexico is not allowed to manufacture guns (or cars). The U.S. Mexican border is often, and correctly, pointed to as the place where all the drugs from South and Central America enter their biggest market: the U.S. But there is not the same amount of attention paid to the fact that it is also the point where all the guns made in American enter one of their biggest markets: Central and South America.

So is it getting better? Anecdotal evidence seems to indicate it is. Everyone insists it is. Violence is down significantly in 2012. Although this might not be because the cartels were defeated, but because all but one cartel was. The Sinoloa cartel now controls the Juàrez territory, which was once heavily disputed. Either way, I didn’t feel the least bit unsafe while walking through the city.

The first night in Juàrez I did my part to dispel any false notions of danger, drinking Tequila a stone’s throw from the border at “Kentucky Club” a cantina where Elizabeth Taylor, Marilyn Monroe, and Frank Sinatra were patrons and that claims to be the birthplace of the Margarita. This is the same place that the Dallas Morning News ran a story about in June of 2010, with the headline “Drug cartel violence may doom famed Kentucky Club.” But on this Saturday night in October, the safest month the city had seen in five years, The Kentucky Club seemed more than surviving. It was thriving, and so was I as I happily smoked cigarettes inside and enjoyed margaritas and the ubiquitous “Juàrez is safe now” pitches fed to me by Mexican girls with beautiful accents and beautiful curves. The place was packed by the time I got a ride back to the hotel. As far as I could tell, Kentucky Club , like Juàrez, itself, is back.

Josh, well researched and it definitely was a great night in Juarez, and I too felt safe for the entire time in Juarez…. I remember those women with beautiful accents and beautiful curves too… all I can say to that is my ah, Chihuahua!

stay adventurous, Craig

Fantastic overview Josh! I’d head back to Juarez in a heartbeat.

Just forwarded the article to the beautiful women you mentioned here… They say HI!

Love it Josh! Fabulous to have shared the experience x Ah Chihuahua!

Very well done—latest stats show that violence has been down down down the last two years and is down 74% in the first 8 months of 2012. It is a new place and it was so much fun to be there.

My highlight was running the streets of Juarez along the border at sunrise with 1500 Mexicans.