Medicine boasts several cases where doctors have experimented with new methods of treatment using themselves as subjects. In the late 1970s, Dr. Barry Marshall challenged the prevailing wisdom that excess stomach acids caused ulcers and was laughed off the stage at a gastroenterological convention for suggesting they were caused instead by bacteria. To prove his point, Dr. Marshall ingested helicobacter pylori, the bacteria in question, and promptly developed an ulcer which was subsequently cured with antibiotics. Earlier, Dr. William Stark’s ultimately fatal experiments with a citrus-free diet led to the discovery that it was the lack of vitamin C which caused scurvy.

There are other examples, some more extreme, some less, where physicians made their bodies their laboratories. The impetus behind this stems from a variety of motives. One of them is the rejection of their ideas by colleagues; another is the desire to shortcut long and prohibitively expensive testing processes. Say someone was to propose experiments aimed at proving human life could be made immortal. That person would very likely come up against both obstacles.

A third thing however that sometimes happens when doctors treat patients, or themselves, is that without necessarily aiming to prove a thesis, they serendipitously arrive at proofs that support one. This is what occurred with noted neurosurgeon Dr. Jacob Rosenstein. As Rosenstein approached his mid-fifties, he noticed that standing on his feet performing surgery for as many as eight hours a day was beginning to take a toll— not just on his body but his mental concentration. Since this was unacceptable to him, Dr. Rosenstein took measures to restore his previous energy. He changed to a more plant-based diet, cut out alcohol and fats, and began a rigorous exercise schedule. In a relatively short period, he was feeling more like his old self.

Of course, many Type A people have done exactly what Dr. Rosenstein did. Where Rosenstein differed from his peers was in his ability to study and, in fact, even quantify the changes he noted in his own mind and body. Early in his age management journey, Dr. Rosenstein had become interested in telomeres, DNA strands at the end of our chromosomes, “which protects the genome, and the entire organism, from nucleolytic degradation, unnecessary recombination…and interchromosomal fusion.” Telomeres are vital to chromosomal health but, like the rest of the body, deteriorate with age, growing progressively shorter and less effective as one ages. Dr. Rosenstein reasoned that if one could reverse this deterioration, one could attack the aging process in general.

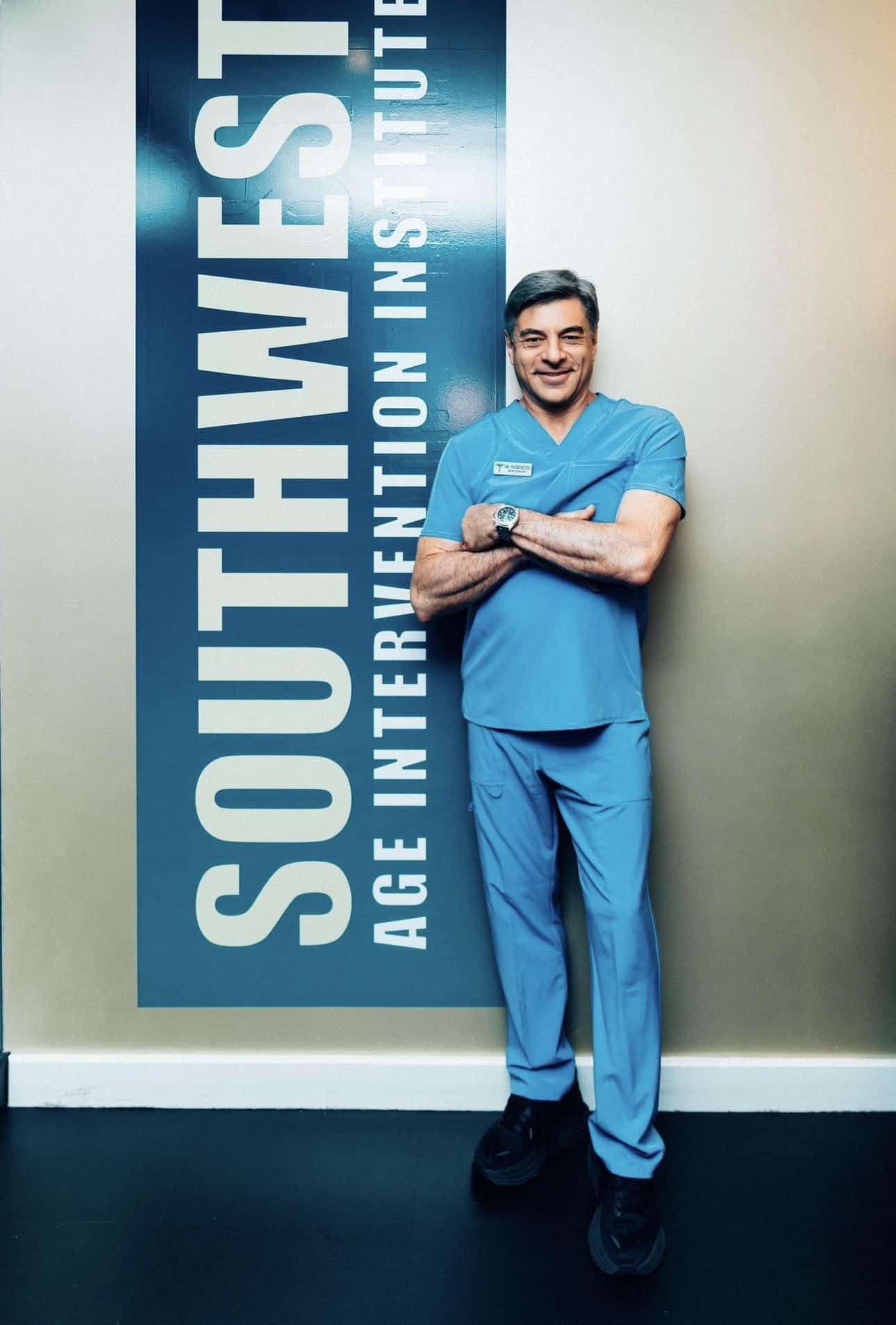

When Rosenstein began to measure his own telomeres, the results were astonishing. By adhering to his transformative regime, he found that at age 54, he had the telomeres of a 39-year-old. Even more astonishing, at 60 his telomeres were those of a ten-year-old and at 64, of a newborn. Assuming that if he could achieve these results so could others, Rosenstein began to incorporate what he’d learned into his practice. In time, hoping to expand his outreach by casting a wider net, Rosenstein went on to found the Southwest Aging Intervention Institute— a facility that combines an intensive intake interview with Rosenstein himself with tests such as a 90 biomarker bloodwork, blood vessel analysis, and iDXA total body composition scans among many other tests. The idea was to use testing to fashion a regime specific to each individual’s needs while serving the common aim of restoring energy, concentration, vitality, libido, and sexual functioning. Those who keep to their regime the Institute proposes, will find themselves rewarded with a more vigorous and youthful physical, emotional, and sexual life.

Quantifying and devising regimes is one thing; feeling renewed is another. Dr. Rosenstein’s current ability to burn the candle at both ends— performing demanding surgery while meeting the additional responsibilities of supervising an institute— testifies to the success of his method for the doctor himself. That his clients continue to be high-functioning leaders testifies to the success of his methods for others. If Dr. Rosenstein is his own best poster boy, he remains quick to tell his patients “Our goal is to have you live to 100 and beyond. And…if you don’t get to 100” while looking good, and most importantly, feeling young, “you’re going to make me look bad.”

To find out more about Dr. Jacob Rosenstein’, read his “Defy Aging: Make the Rest of Your Life the Best of Your Life.” To learn more about the Southwest Age Intervention Institute, visit its website.